Inside the Minds of The Veterans Ready for War

As Election Day approaches, veteran militia members, bikers, and other radicals are ramping up violent rhetoric

Last May, Artie Muller, a reactionary Vietnam War veteran, threatened action should House Speaker Nancy Pelosi move to impeach President Donald Trump.

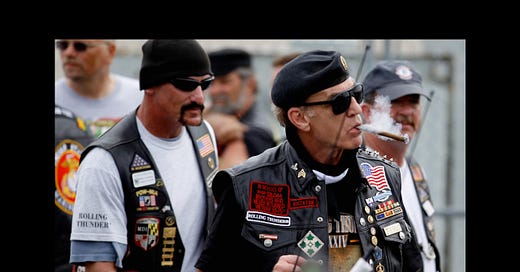

Muller — featured on the right in the photo above — characterized Pelosi to the press as an “arrogant little bitch.” He also pledged to organize a rip-roaring crew of veteran bikers to descend on Washington D.C. and defend the president should she get in his way. “I think [Trump’s] doing a great job, and I wish Nancy Pelosi and her cronies would get off his back,” said Muller, the long-time executive director of Rolling Thunder, a veteran biker charity focused on bringing public awareness to Prisoners of War (POW) and those Missing In Action (MIA).

Muller — whose leather biker vest includes patches reading “Jane Fonda: American Traitor” and “DICTATOR” — didn’t make good on his threat after Trump was impeached. But he certainly could have.

For decades, Muller’s organized massive Rolling Thunder rallies in D.C. that have attracted as many as 1 million riders, many of whom are on the Trump Train. For those, like me, who’ve never been to a Rolling Thunder rally and are eager to understand its atmosphere, I’d recommend the country song below, which describes the event as a “tattoo rendezvous, Woodstock with an attitude.”

Veterans and bikers are two of Trump’s most diehard constituencies. They come together under the banner of Rolling Thunder, but also inside the “Bikers for Trump” a loosely organized group that conducts informal security at Trump rallies. A third fringe organization called 2 Million Bikers to DC was founded in 2013 to organize counter protests to the Million Muslim March. Many of the 75,000 bikers who showed up to that event roared their engines over attendees and yelled “USA! USA!" and "Get out!"

Muller’s easily the most powerful veteran biker in America. Over the years he’s helped pass federal legislation banning protests at military cemeteries and mandating POW/MIA flags fly in Washington. While Muller hates former President Barack Obama, he’s enjoyed warm relationships with other commanders-in-chief, including George W. Bush, and Trump.

For Muller and Rolling Thunder to rev so hard for Trump is bizarre. After all, Trump, in describing his disdain for John McCain, literally said “I like people who weren't captured.” More recently, Trump removed the POW/MIA flag from atop the White House to a less conspicuous spot on the South Lawn, which elicited anger.

Yet Trump’s overwhelming jingoism has won the veteran biker crowd over. Muller said he’s spoken on the phone with the president a half-dozen times, including a call last month where they discussed a planned rally for November 11 — Veterans Day.

Muller, like many on the right, speaks ominously of the days after the election should the presidential outcome remain unclear, or if Biden wins. Muller told me he takes pride in the fact that Rolling Thunder rallies have always been peaceful, and said he wanted the Veterans Day event to be similarly calm. “We don’t need mayhem in the country. We really don’t need it,” he said. “But I don’t have control of everybody, and theres a lot of militia groups out there. And they are 100 percent behind this country.”

Later in our conversation, Muller pivoted to more violent rhetoric. “If need be, I would take up arms to protect this country,” he said. “It’s getting close to a civil war with the bullshit that’s going on. This isn’t just me, I talk to a lot of high-ranking officers in the Pentagon and they feel the same way. Something’s going to happen if things don’t straighten out.”

A minute later, while on a tangent about his perceived persecution of the cops, Muller essentially called for the murder of civil rights protesters. “If it was up to me I’d take a machine gun out there and take some of ‘em out,” he said. “That’s the only way they’d learn. It’s the only way to make sure we have a free country.”

The likelihood of Muller — a stiff, 70-something with nerve damage stemming from his exposure to Agent Orange — heading viciously into battle is unlikely. Even so, his rhetoric is indicative of many veterans on the right who are gearing up for a fight.

Trump seems ready to activate them. Last March, he ominously warned that the bikers, veterans, and other hard-edged believers in the MAGA way would react first should his political foes cross him. "I have the tough people, but they don’t play it tough — until they go to a certain point, and then it would be very bad, very bad," he said.

In her excellent book “Bringing the War Home,” Kathleen Belew traces veterans’ outsize role in domestic terrorism back to Vietnam.

Far before that, of course, those who served were integral leaders in the patchwork of American militias and hate groups. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), after all, was started by a group of Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee. Belew’s research shows that spikes in vigilante violence and KKK membership throughout American history aligns most perfectly with soldiers coming home from battle. “All of American society turns more violent after warfare,” she declared in a 2019 talk.

Yet for a number of reasons, Vietnam served as the most powerful catalyst of the white power movement. For one, this was the first major war with an integrated force. As such, white service members inflicted deep pain and suffering on their comrades of color, including murders and Klan actions on bases in America and Southeast Asia. In one brazen 1976 incident, a crew of Marines at Camp Pendleton wore KKK patches and held Klan meetings on base.

Vietnam was also the first modern war in which America was humiliated by a non-white enemy. This thoroughly scrambled the psyche of the American warrior, and led to deep disdain and distrust of the American government. It also led to a fictionalized and radical recasting of the war to keep up the air of western superiority. The Vietnamese were simultaneously dehumanized, in large part through the POW/MIA movement, which claimed, without evidence, that scores of American soldiers remained in brutal custody after the war ended. (As historian Rick Perlstein has explained, President Richard Nixon first concocted the POW/MIA myth “in order to justify the carnage in Vietnam in a way that rendered the United States as its sole victim.”)

Muller obviously ascribes deeply to the POW narrative, and feels that the enemy he fought was fundamentally evil. In 2003, for instance, he admitted to the The New York Times that he burned down Vietnamese villages, an act he believed would save American lives. (It’s also worth noting that Muller’s group, Rolling Thunder, is named after a brutal, blanket-bombing campaign that killed tens of thousands of civillians.)

The common sense of betrayal forged out of Vietnam fostered an environment where a slew of anti-government and hate groups could coalesce. Service members are trained in American conquest, and are motivated to kill under the guise they are dominating one evil government or culture and replacing it. Because Vietnam had denied them this feeling, many turned to the home front in a twisted attempt to accomplish their mission.

This class of aggrieved, angry veteran extremists included Louis Beam, a helicopter door-gunner in Vietnam who became a KKK and militia leader. (An early target of Beam’s was proposed government support for Vietnamese immigrant fishermen.) There was also Glenn Miller who, according to Belew, served two tours in Vietnam as a Green Beret only to be discharged in 1979 for distributing racist literature. (Miller went on to became a major force in white power organizing and, in 2014, killed three people inside a Jewish Community Center in Kansas.)

These and other Vietnam veterans built up a strong but leaderless network that a new cohort of former service members joined. One of them was Gulf War veteran Timothy McVeigh, whose 1995 bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City remains the deadliest act of homegrown terror in American history.

Belew’s book desperately seeks to recast our collective understanding of terrorism around the Oklahoma City Bombing, and white extremism. She further warns the reader that while the September 11th terrorist attacks elicited a massive federal effort to root out and suppress extremism abroad, only piecemeal, largely ineffective efforts have been launched to squelch hate on the home front.

Our current era of the War on Terror strikingly mirrors Vietnam, and what came after it. First is the glaring fact that neither conflict was “won.” Both were justified by lies, and increased mistrust of government. Vietnam technically lasted 19 years, the same age as of our Forever Wars today.

Even smaller narrative details align. Just as lots of military equipment and weaponry waas stolen from bases in the wake of Vietnam, similar snatches are happening these days. Just as dozens of Navy sailors felt comfortable to pose with the Klan in 1923, a Marine Corps scout sniper team in Afghanistan felt emboldened in 2012 to snap a photo in front a Nazi SS flag.

While the previous generation was radicalized on LibertyNet, a crude message board founded by Beam, the post-9/11 generation has a multitude of online platforms like Stormfront and 4Chan. And while the agricultural crisis in the 1980s brought land workers into the hate movement, there are renewed fears today of “white supremacy at the farmers’ market.”

Most alarming these days is the sense that something far bigger and more destructive than the pockets of violence we’re seeing is in the works. Indeed, the frequency of violence is increasing, as are the number of Americans — and veterans — willing to engage. The stupefying potential of this violence was made crystal clear by The New York Times, which recently estimated that “veterans and active-duty members of the military may now make up at least 25 percent of militia rosters.”

This trend was further fleshed out in a recent Atlantic report that revealed a roster of roughly 25,000 militia members in the Oath Keepers. (Nearly two-thirds had a background in law enforcement or the military.) The story quotes a number of them, including one Marine who posted on internal chats that “I will not go quietly into this dark night that is facing MY beloved America.” Another marine named Joe Klemm, who runs a splinter militia called the Ridge Runners, is quoted as actively spoiling for war. “I will tell you that peace is not that sweet,” he said. “Life is not that dear. I’d rather die than not live free.”

Over the last four years there have been current and former service members linked to a plethora of violent hate groups like the Atomwaffen Division, plus the Proud and Boogaloo Boys. Meanwhile, the neo-Nazi group “The Base” is now actively recruiting people with military expertise in the U.S. and Canada “to train in military operations and prepare to take advantage of what they believe is impending societal collapse.” (On Twitter, veteran and former VA official Kayla Williams pointed out the deep irony in a bunch of vets joining up to The Base, which, translated to Arabic, is “Al-Qa'idah.”)

It can be enticing to think that these looming threats of domestic terrorism are overhyped by the media. Seeking an expert perspective, I reached out to Ed Beck, a Marine veteran who doxxes extremist vets in his spare time.

He expressed increasing worry over the activity he’s seeing, both in the streets and online. Some of the most concerning rhetoric he hears comes from old pals from the service. “I think we are at a 5-alarm fire at this point,” Beck told me. “I don’t think its possible to be too alarmist about this stuff.”

In recent months, Beck’s flagged the activities of a whole host of nutcases, like American Legion member Dennis Riggs, a neo-Nazi arrested in January for illegal possession of seven firearms, and Gregory Isaacson, an alt-right Marine vet with ties to the Proud Boys, Patriot Prayer, and Identity Evropa.

In 2017, Beck contacted military police after gathering enough evidence to suggest that a 21-year-old lance corporal in the U.S. Marine Corps named Vasillios Pistolis was deeply involved in neo-Nazi and white supremacist activities. According to ProPublica, the Marine Corps didn’t follow up on Beck’s well-documented tip for months. (Following pressure stemming from ProPublica’s reporting, Pistolis was eventually court-martialed, imprisoned, then booted from the military.)

In our interview, Beck concisely laid out both the obvious and more complicated reasons for veterans joining these hate groups. “Joining the military is in some ways a radicalization process, albeit to patriotic ends” he explained. “You are conditioned to become comfortable with violence and doing extreme things. There’s also a rush to that edginess.”

Beck also made the important point that the radicalization of vets, and anyone else, for that matter, cannot be isolated from the broader GOP shift towards violent rhetoric, and fascism. Republican lawmakers, after all, defended the Kenosha shooter, Kyle Rittenhouse, and the president recently told the Proud Boys to “stand by.” Far before this, in 2009, the Republican Party and the American Legion publicly slammed a Department of Homeland Security report that warned of growing links between military veterans and domestic terrorism. According to Politico, this backlash halted federal work to stem veteran hate.

The process for turning down the heat, and the hate, in this country, will be incredibly difficult. One instructive case comes in the tale of Chris Buckley, an Army veteran and former KKK member who renounced his racism and is today best friends with a Syrian refugee, Dr. Heval Kelli. Buckley’s transformation is owed to the miraculous work of Life After Hate, an organization of former skinheads looking to bring harmony to the world. Days before Trump was inaugurated, the Obama administration awarded the organization a $400,000 grant. Shortly after Trump took office, the money was rescinded.