May Day, My Dad + The Problems of a Movement Messiah

The movement to end the Vietnam War could have morphed into something larger. What went wrong?

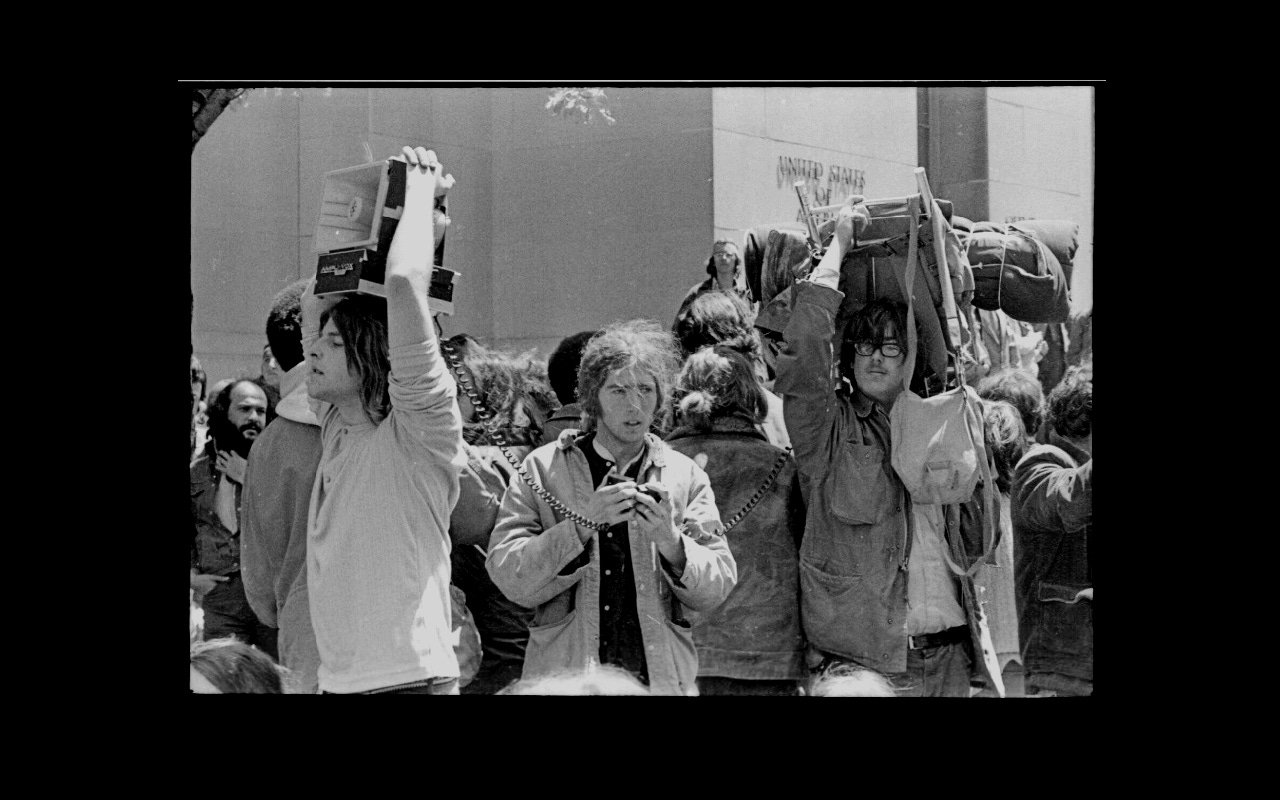

My dad, Jay Craven, spent much of May 3, 1971 zipping around Washington D.C. with storied anti-war activist Rennie Davis, checking in on merry bands of Mayday protesters they helped galvanize under a unifying credo: “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government.”

In Georgetown, Davis and my dad checked in on a gaggle of shaggy protestors, arms linked to obstruct the intersection of Wisconsin Avenue and M Street. When a platoon of cops descended on motor scooters, the activists scattered to another site four blocks down. At DuPont Circle, my dad caught a glimpse of Pete Seeger strolling among hundreds of protestors preparing to tie up traffic on the rotary. Seeger’s banjo, slung over his back, carried the neatly hand-scrawled message: “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender.”

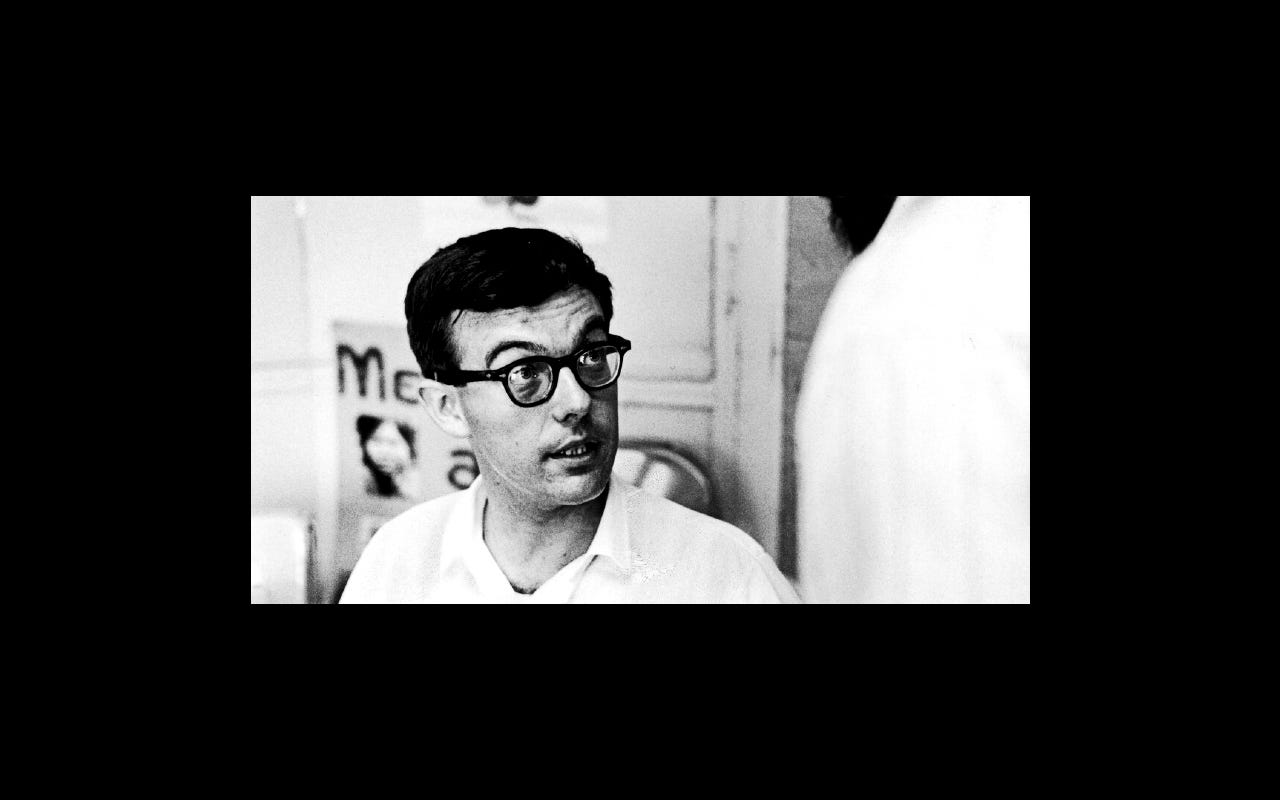

Then 20, my dad was little more than a kid. But his work against the Vietnam War as Boston University’s student body president had caught the eyes of Davis and Dave Dellinger, two members of the famed “Chicago 7.” In November 1970, the pair called my dad to D.C. for an interview where Davis articulated the urgent stakes of the war in titanic terms. Dellinger, between sips of whiskey and puffs from a Cuban cigar, peppered him with questions about his background and willingness to spend some time in jail.

“Are you sure you’re ready to make this commitment?” Dellinger asked my dad.

“Yeah, I guess so,” he replied, eager but overwhelmed.

That December, my dad and fourteen fellow student leaders visited Vietnam and forged a “People’s Peace Treaty” with Vietnamese student leaders. The idea was to show common cause and put pressure on President Richard Nixon’s highly secretive and mostly sclerotic Paris peace negotiations. During this trip, my dad also captured film footage of mountain islands on the Vietnamese coast and babies suffering severe injuries from exposure to Agent Orange. His film ended up in a quasi-Newsreel documentary, “Time Is Running Out,” that motivated people towards the Peace Treaty and Mayday.

After returning to the states, my dad essentially dropped out of college to fight the war full-time. Davis deployed him to peace groups and college campuses across the country, where he gave speeches, showed the film, and recruited members into a “Mayday tribe” that would converge on Washington that spring to make trouble. Ahead of the protest, members were given little more than a tactical manual that detailed specific traffic chokepoints that affinity groups from each region were expected to immobilize. Also included were poetic explainers of the movement’s goals. “Mayday is action, a time period, a state of mind and a bunch of people,” the manual reads. “Be free.”

Mayday was the concluding event of a 17-day “Spring Offensive” against America’s seat of power. It featured mass protest rallies, traditional lobbying, targeted sit-ins and Vietnam veterans discarding their military medals at the foot of the Capitol. (There was also plenty of hanging, lots of pot and LSD, and performances by the Beach Boys, Linda Ronstadt and Charles Mingus at the movement’s base camp in West Potomac Park.)

From his “Western White House” in San Clemente, California, Nixon obsessed over Mayday and became hellbent on disrupting the plans. Hours before the action was set to begin, a sturdy phalanx of riot police broke up the park encampment, leaving thousands without a place to stay. While some bounced from the city, many found places to crash, including churches and college dorm rooms.

As May 3rd dawned, roughly 45,000 people flooded the streets in a guerilla-style incursion. Protesters blocked roads with their bodies and assorted junk cars, handed out anti-war flyers to bureaucrats stuck in traffic, and dumped chicken shit on the steps of the Pentagon.

Davis was the brains behind the idea to “stop the government,” though this gambit was clearly inspired by countless civil disobedience actions by the civil rights movement and an aborted plan by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to tie up traffic at the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

Mayday leadership was largely white and male, though not without women and a strong contingent of gay liberationists. Most impressive was the ideological and geographical diversity on display. Mingling in the streets that day were Vietnam veterans and Quaker pacifists, students and academics, Yippies, burnouts, potheads, and pranksters. Many were first-time demonstrators, others were movement messiahs like Howard Zinn, Abbie Hoffman, Dan Ellsberg and Noam Chomsky.

This collective swell of intensive and unpredictable energy spooked Nixon, who unleashed nearly 20,000 police, National Guard, Army, and Marines to execute the biggest mass arrest in American history. “Anyone and everyone who looked at all freaky was scooped up off the street,” one protester observed after 13,000 people had been scooped up.

Our nation’s capital was engulfed by tear gas, swarms of billy clubs and huge Chinook helicopters disgorging Marines onto the grounds of the Washington Monument. Mayday raised the stakes for the Nixon regime and effectively brought the war home, especially when considered in concert with the Vietnam veterans’ actions just ten days earlier. At one D.C emergency room, a vet caring for bruised-up kids observed, “it’s another Saigon.”

Mayday was messy and chaotic, but it had an impact. According to journalist Lawrence Roberts’ illuminating new book “Mayday 1971,” then-Secretary of State Henry Kissinger broadly summed up the Spring Offensive as “our nightmare, our challenge, and, in a weird way, our spur.” Former CIA director Richard Helms similarly admitted that Mayday put new pressure on the administration to “try and find some way to get out of the war.” Indeed, the Nixon administration’shardline conditions at the Paris Peace Talks softened dramatically in the immediate aftermath of the protests.

Mayday also cemented a series of important legal precedents regarding peoples’ rights to protest and peaceably assemble. Thousands locked up during these three days of action not only saw their charges dismissed but also became some of the only U.S. citizens to ever receive financial compensation for these violations of their constitutional rights.

Despite all this, when Davis spoke to members of the media on Mayday’s dramatic first afternoon, he expressed frustration that the protests hadn’t sufficiently gummed up the government’s works. “We failed,” he announced.

This declaration infuriated my dad. He and an older Mayday coalition leader, Sid Peck, openly disagreed, but to no avail. The press grabbed Davis’ two-word post-mortem and ran with it. While some journalists reported favorably on the day’s actions, most were let off the hook of more serious consideration when Davis waved the white flag of defeat, much to Nixon’s delight. In the blink of an eye, the Vietnam peace movement’s most potent display of decentralized organizing was sold short by its most public leader.

“One advantage for the movement – media celebrities minted and lionized during the Chicago 7 trials – also proved to be a liability,” my dad recently told me. “Rennie valiantly served this historic moment – by conceiving and articulating a powerful vision for it on the stump. But he failed to truly recognize or understand what he had set in motion – or where it could have gone from there.”

My dad remembers pushing Davis and others to build on the energy witnessed at Mayday. He wanted to facilitate fresh organization to leverage new contacts, new strategies, and a new generation into a regionally based movement that could fight the “Pentagoons,” but also address issues around racism, poverty, and power.

According to my dad, Davis initially rejected the idea, and, more broadly, neglected the movement. He failed to attend a post-Mayday post-mortem in August 1971 and, later that year, executed a disastrous “Evict Nixon” rally that only attracted 1,000 participants. After that failed event, Davis expressed more openness to the idea of a new organization. “We can try,” my dad responded. “But I think it might be too late.”

The American 20th century was blessed with mythic leaders who could both organize and inspire, among them Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Fred Hampton. And yet after they were assassinated, their movements lost steam.

There have long been voices cautioning against deifying leaders, most notably Ella Baker, a tenacious but underappreciated organizer who served in numerous civil rights organizations and led the “Freedom Rides.” Baker prioritized empowering the collective and she declared that “strong people don’t need a strong leader.”

Davis was a strong leader who surrounded himself with strong people. But the power of his celebrity meant that when he faded from the scene, the movement declined. After Mayday, Davis became a shadow of his former self and, in early 1973, became the spokesman for 15-year-old Indian guru, Maharaj Ji. (Davis died of lymphoma in February, at the age of 80.)

Davis was gifted with a silver tongue, a rich political imagination, and a penchant for mobilizing. He was also a talented mythmaker and a media darling. In his book, Roberts reports on a pre-Mayday lunch at the Washington Post in which Davis, “with his poise and knowledge, won over the skeptical editors and reporters who came armed with questions about Vietnamese history to trip him up.”

Richard Flacks, an early compatriot of Davis’ inside the Students for Democratic Society (SDS), ribbed his pal for using “smoke and mirrors” but described him as highly gifted in “political salesmanship.” Many bought what he was selling, including my dad.

Davis entered the movement for peace and racial justice in the early 1960s as a student at Oberlin College. He teamed up with fellow SDS pioneers Tom Hayden, Paul Potter and others to build a powerhouse political movement on campuses across the country.

Yet as his celebrity grew after the 1968 Democratic Convention and subsequent Chicago 7 trial, his conception of himself seemed to change. Some felt he became too beholden to optics and the media. (Take Davis’ personal webpage, where he brags that the Chicago tumult was “watched on television by more people than watched the first man landing on the moon.”)

The media, of course, play an outsize role in swaying public opinion and influencing action on policy. But no movement’s work should be measured by how well it plays to a TV audience. Activists must stay tuned in to the people, not the pundits, and raise the stakes in ways that cable executives may not endorse.

Ironically enough, one of the figures most critical of Davis’ celebrity was John Lennon, a man more famous than Jesus. In 1972, as the movement flailed and Nixon prepared for his re-election, the former Beatle agreed to perform a series of swing-state rock n’ roll concerts for the peace movement. One fantastic event materialized, in Ann Arbor, Michigan featuring Stevie Wonder, Sha Na Na, and others. The concert was billed mostly as a “freedom rally” for political activist John Sinclair, who was then serving ten years in jail for possession of just two joints– and had been repeatedly denied parole. Within three days of the concert, Sinclair was released and hopes for a movement renaissance, propelled by Lennon’s star power, took root.

Yet the Nixon White House swiftly placed Lennon and Yoko Ono under round-the-clock surveillance and initiated deportation proceedings. The peace tour fell apart as Lennon became uncomfortable with the government’s squeeze. According to his memoir, Lennon was also turned off by Davis and other movement heavies he described as “big mouth revolutionary heroes” who were only against things, never for them. “None of them knew how to talk to the people, never mind lead them,” Lennon observed.

In the end, the movement failed to spur energy behind George McGovern, whose ass got kicked by Nixon. Peace in Vietnam was declared in 1973 – and achieved in April 1975, yet many other pressing issues remained. Even so, Davis dropped out, in service of the guru. In 1974, Playboy caught up with Davis proselytizing for Maharaj Ji on Stanford’s campus. “Join me in crawling on my belly, if necessary, across the surface of this earth to kiss the lotus feet of the Guru Maharaj Ji,” Davis is quoted as saying.

The Playboy profile – written by Robert Scheer and titled “Death of a Salesman”— goes on to describe Davis as living a “rarefied life” that was “so divorced from the stuff of ordinary human existence that his politics had become a game.” It further contended Davis had surrendered himself to the “fickle and co-optive forces of the media,” a process that “destroys any real roots, anger, love or joy in the speaker-leader” and “substitutes contrivance for spontaneity and press notices for human affection.”

A resurgence of political activism is unfolding today and the strongest movements of late have been fluid and, at least publically, “leaderless.” As such, they’ve been generally immune from threats of arrest, assassination, or shifting ideologies. Most are galvanized not by the words of a single leader but a simple call to action on social media. These movements include the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, the Yellow Vests, the pro-Democracy activists in Hong Kong, and perhaps the most successful domestic movement of the moment: Black Lives Matter.

Many Mayday participants, including my dad, see Black Lives Matter as learning the right lessons from 1971 and the civil rights movement more broadly. These protestors, after all, have often embraced civil disobedience that remains remarkably nonviolent. They’ve also formulated unsparing rhetoric and made lofty demands – including not only stopping an arm of the government, but abolishing it entirely.

This behavior has elicited skepticism in the media, yet it has empowered tens of thousands of new activists while fundamentally shifting perspectives and behaviors around racism and police brutality. A March study found, for instance, that the cities and town with the most active Black Lives Matter activity saw both decreases in police homicides and increases in the use of body cameras and community policing tactics.

While academics and journalists have deemed this recent wave of recent activism as “leaderless resistance,” Patrisse Cullors, who first coined Black Lives Matter as a Twitter hashtag, views BLM’s success as a result of building a “leader-full movement,” where every participant has agency and voice – for local action and control,

“I don't believe you can do anything without leadership,” Cullors told NPR in 2015. “I don't believe that at all. I think there are many people leading this conversation, advancing this conversation...There [are] groups on the ground that have been doing this work, and I think we stand on the shoulders of those folks.”

Drugs interfered