The Last Gasp of the Conservative Veteran Complex

A diverse crop of progressive veteran advocates is slowly but surely replacing the old guard

In late January, as it became clear that current and former military members played an outsize role in the Capitol invasion, a diverse chorus of younger veteran voices demanded a long-overdue reckoning of extremism in their ranks.

In an exciting cross-generational moment, gatekeepers inside some of the most powerful Veterans Service Organizations (VSOs) heeded this request. Some pledged to systematically root out and boot out any members connected to the riots.

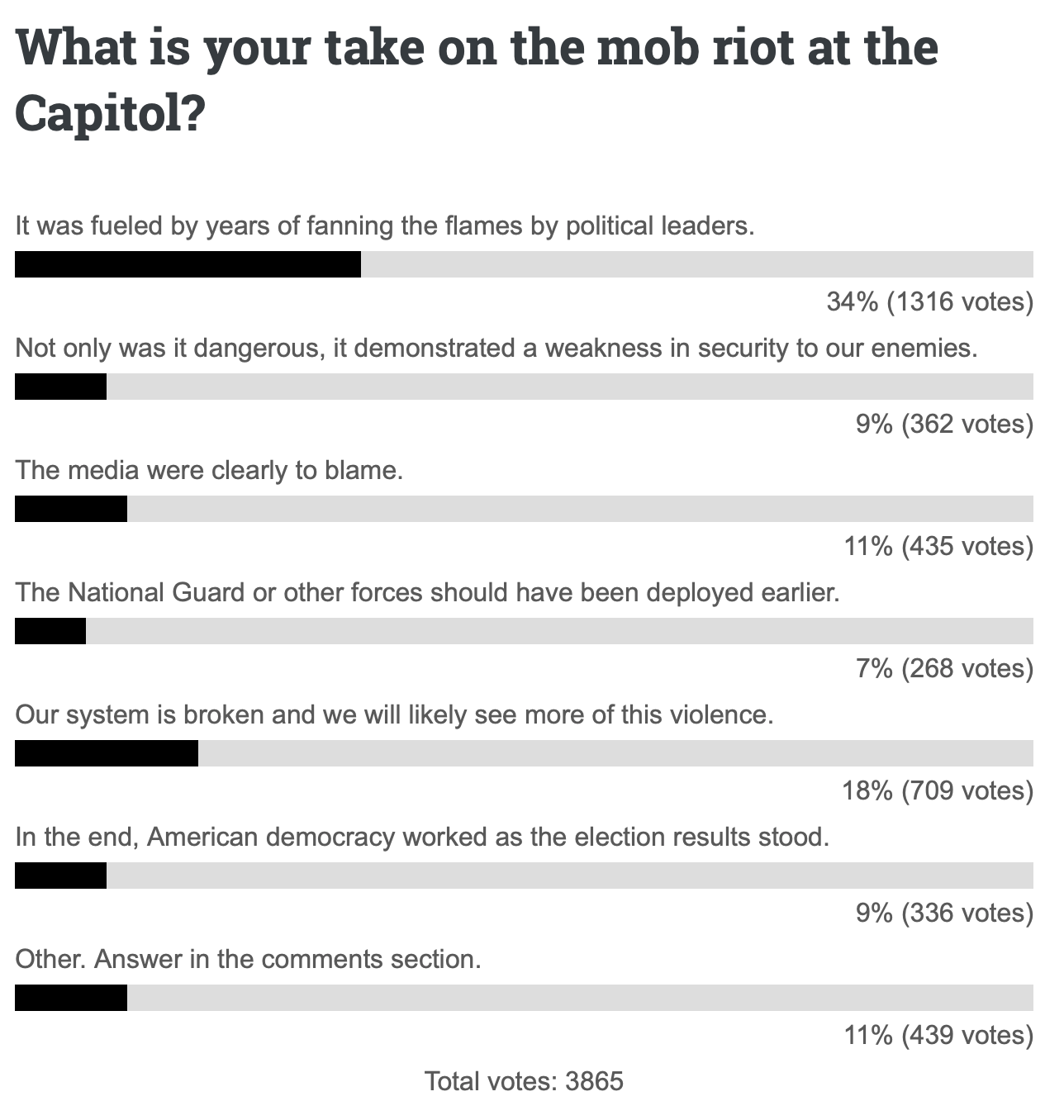

The world’s largest veterans group — The American Legion — decried the day’s violence. But the Legion’s spokesperson, a right-winger named John Raughter, said the organization would take a passive approach to punishment, leaving personnel actions up to local post leaders. The Legion also circulated an online poll about the riot that sidestepped many of its underlying causes:

In comments accompanying the poll, Legionnaires contended that “traitors” connected to “Antifa” and “Black Lives Matter” were the ones who fomented violence. Some alleged that the 2020 election had been stolen from Donald Trump. One clear-eyed commenter pointed to the Legion’s poll as politically toxic and dangerous. “This type of ‘poll’ promotes misinformation and divisions within our membership,” he wrote.

Perhaps the sharpest critique of the Legion’s muted response to the violence of January 6th came from one its former members, Lindsay Church, who now runs Minority Veterans of America.

“Watching the flags of the American Legion fly on the steps of our Capitol during this insurrection, after personally resigning from their ranks years ago due to rising white nationalism and racism, brought me to my knees,” they wrote. “For the past several years, leaders in the veteran community have been ringing the alarm bells of radicalization within our ranks while folks gave passes to organizations that have harbored white nationalists in leadership positions. This must end now.”

Ending such practices does not, however, seem to be on the Legion’s agenda. For many decades, innumerable non-white, non-male veterans were denied full status inside the Legion. One of them was World War II veteran Gladys “Bunny” Strong, who, after 70 years of waiting, was granted a bona fide Legion membership in a 2015 ceremony. Weeks later, Strong died, at the age of 92.

That same year, Church was elected commander of their Seattle Legion post. They were grateful to be given the position and worked earnestly to update the place’s culture. But Church’s efforts at reform proved impossible.

One day, a male member told Church: “It’s OK that you’re gay, but you don’t need to talk about your wife.” Some of the young women Church brought into the post were asked out on dates or otherwise made to feel uncomfortable. “I kept telling my friends, ‘It’s going to get better,’” Church told me for a 2020 story about the Legion’s regressive culture. “But I was harming my people, and it weighed on me. One day I realized that my work was perpetuating an old school mentality, so I left.”

Church’s experience is hardly the exception. Many female and minority veterans are still verbally harassed by Legionnaires or altogether shut out from local posts. This behavior isn’t altogether surprising, as Legion leadership has long been complicit in enabling prejudice.

In 2009, for instance, the Legion joined the Republican Party in publicly slamming a Department of Homeland Security report that warned of growing links between military veterans and domestic terrorism. According to Politico, this backlash halted federal work to stem veteran hate.

More recently, a cast of white supremacist Legionnaires has emerged. They include Joseph Kane, who has Identity Evropa connections, and Dennis Riggs, a neo-Nazi arrested last year for illegal possession of seven firearms. Two days before the January 6th attacks, the Legion kicked out a national leader who, according to the Los Angeles Times, “bragged on social media about participating in a street brawl and joining the Proud Boys.” (While other VSOs have generally done better than the Legion in supporting diverse voices, the Veterans of Foreign Wars defended a Connecticut post leader in 2018 with a documented history of hate crimes and involvement in the Ku Klux Klan.)

There are, of course, many Legion leaders at all levels who, like Church, earnestly want to update the culture. In Portland, Oregon, for instance, legionnaires opened their hall to homeless citizens, installed gender-neutral bathrooms, and operated LGBTQ trivia nights.

Yet many other Legion leaders — including some young ones — have dismissed concerns about extremism and stuck to outdated thinking. One is Jason Secrest, a Lieutenant Colonel in the New York National Guard and the commander of the Legion’s Washington, D.C. post. In a recent podcast interview, Secrest aggressively (but inaccurately) attacked my reporting on the Legion’s dark past. “When you know history like I do, you know that it’s bullshit,” Secrest said. He continued:

Like [Craven] talks about, ‘Oh, The American Legion invited Mussolini to speak at a national convention.’ Well, okay, back in 1930. If you have a grasp on history, you understand history, you’re in the early part of the depression … well, Mussolini was the man who made the trains run on time. I mean, that’s the old anecdote. And he took a war-ravaged, poor country and kinda put it back on track. Now he used bad methods, but a lot of those weren’t known to the public at the time.

In truth, Mussolini built a militant squad of “Blackshirts” by the early 1920s that tortured and killed thousands of working people. This campaign of unjustified violence was detailed by the Legion in a 1923 puff piece on Il Duce.

The point here is that many in the Legion — and in other conservative veteran groups— aren’t willing to rethink their positions or share power with anyone outside their tribe. And while many of these vets got a kick out ofTrump’s presidency, the Legion and other old-school vet groups now face deep financial issues and aging members. They can adapt or die. Either way, Church’s generation will soon be calling the shots.

Church co-founded Minority Veterans of America (MVA) in 2017 as a small 501(c)3 built for “underrepresented veterans, including womxn, people of color, LGBTQ, and religious minorities.” That first year, the group raised just $12,000, and was essentially run as a volunteer outfit from Church’s living room.

MVA found few allies in Trump’sWashington. Members watched in horror as the president imposed a ban on transgender military service then appointed as VA Secretary Robert Wilkie, the man who helped craft and enforce this discriminatory policy.

Wilkie, a neo-Confederate with a history of racist and homophobic behavior, did little to support to needs of non-white, non-male veterans. He repeatedly refused to update the VA’s motto to be more inclusive and rebuffed efforts to remove Nazi symbols and tributes to Adolf Hitler from the graves of German prisoners in VA cemeteries. He also allegedly sought to discredit Navy reserve officer Andrea Goldstein after she was assaulted at the Washington D.C. VA hospital and allowed a virulent culture of racism to thrive at VA facilities across the country. “The last administration was outright exclusionary and discriminatory to many veterans,” Church recently told me.

These and other vicious attacks galvanized minority veterans, and helped Church quickly expand MVA. Today, the group runs on a $500,000 budget with roughly 2,000 members. The non-profit is now building chapters across the country, ramping up policy work, and offering programmatic support, like VA case management and direct aid, including over $66,000 given in pandemic relief to 300 families.

While the Legion’s current slate of leaders is almost entirely white, MVA just appointed a historically diverse board of directors. One of them is Laila Ireland, a retired Army combat medic who became an early advocate for the rights of transgender troops.

In an interview, Ireland ticked off a number of pressing policy priorities, including ending military sexual trauma, codifying the repeal of the transgender service ban, repatriating deported veterans, and pushing VA to fund and perform gender confirming surgeries. “We are building an intersectional movement of all colors and backgrounds, a collective voice capable of creating critical change in the veterans community,” she said. “We’re striving to be the most inclusive and equitable community in the country. Period.”

While Church knows that powerful actors, including the Legion, still hold enormous sway over veterans policy, they expressed guarded optimism that the new VA Secretary, Denis McDonough, seems willing to listen, learn, and act.

“McDonough met with us within his first three days on the job,” Church said. “It’s not going to be a perfect relationship — there’s a lot of work to do to and it will take a while to build back trust. But it was a powerful step.”

In his nomination of McDonough, President Joe Biden did not break the long streak of white male VA secretaries. McDonough has worked to make up for that by surrounding himself with a diverse crew of senior advisers and conducting a department-wide policy review to ensure that current medical practices are not discriminatory.

McDonough is also clearly listening to a broad swath of veterans advocates, including MVA. Terrence Hayes, the new VA Press Secretary, recently assured me that such engagement is a major focus of Ray Kelley, the VA’s new VSO liaison.

McDonough’s new hires include Melissa Bryant, a Black veteran and ace policy expert who quit the Legion last summer after the organization compared the Black Lives Matter movement to a “virus” that, if unchecked, “could cause more long-term destruction than COVID-19.”

There’s also Kayla Williams, a former U.S. Army intelligence officer, who, despite a much-lauded tenure as director of VA’s Center for Women Veterans, was essentially pushed out of the department under Trump. Williams pioneered projects to make the department more welcoming for women.

While the VA is far from perfect in dealing with the health needs of female and minority veterans, it generally outperforms the private sector. A recent groundbreaking Stanford study found that veterans who were treated inside the VA system during and immediately after an emergency had a 46 percent reduction in 28-day mortality. This “VA Advantage,” as the researchers dubbed it, remained stable for the ensuing year and was as large for Black and Hispanic veterans as for non-minority ones.

Meanwhile, while COVID-19 has wrought outsize damage on Black and brown communities, research shows that minority veterans were more likely to be tested for COVID-19 than white veterans, and that 30-day COVID-19 mortality rates in VA did not differ by race or ethnicity.

Many of the most pressing concerns around disparities today concern VA benefits. Some were outlined in an op-ed last month by Jeremy Butler, the CEO of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America.

“As a Black veteran, I am heartbroken by the failed promise of our nation to honor our troops of all colors and backgrounds with the services we have earned,” Butler wrote after ticking off a series of troubling economic data points on how minority vets have fared under COVID-19. “As the pandemic exacerbated stress on a community already burdened by historical inequity, we must prioritize support for those who are suffering the most.”

This work has become a major focus of the Black Veterans Project, led by former combat medic Richard Brookshire. He and the Yale Legal Clinic recently submitted a massive public records request for benefits and other VA data to identify disparities and discrimination. In addition, the Government Accountability Office will soon begin digging into systematic racism issues inside the VA. In his first press conference, McDonough promised me he would cooperate with this work. “This question about racial inequity [within VA] is one that we’ve had some conversation about,” he said. “So, I appreciate that being out there.”

Butler, Church, Brookshire and others are pushing additional initiatives which focus on important symbols that reinforce gender and racial discrimination. They want, for instance, to change the VA’s motto to be gender inclusive and strike the name of Confederate eugenicist Hunter Holmes McGuire from a VA facility in Richmond, Virginia. (There are other VA facilities honoring bigots, including a Georgia hospital I recently wrote about in the New York Times whose namesake is Carl Vinson, an adamant Neo-confederate.)

Completing this new landscape at the VA and in the world of VSOs are strong allies in Congress. They include House Veterans Affairs Committee Chairman Mark Takano, who first invited MVA to testify along with other VSOS in 2019. Takano also spearheaded the creation of the Women Veterans Task Force, and has now authored legislation that would create a similar commission to study discriminatory policies towards the nearly 2 million LGBTQ+ service members and veterans.

Takano’s Senate counterpart, U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, is more moderate, but recently authored and passed legislation that both eliminates VA copayments for Native American veterans and establishes an Advisory Committee on Tribal and Indian Affairs. (As Stars & Stripes reported in 2019, the VA has a history of restricting care and benefits to Native Americans, who’ve served at higher rates than any other ethnic group.)

There are many other signs of progress that won’t fit inside this newsletter — from inclusionary anti-war organizing inside groups like Common Defense to promises from General Lloyd Austin, the first Black Defense Secretary, to rename bases honoring Confederates and ridding the ranks of extremists. Just yesterday, Yale released a report detailing racial inequities in nominations to the nation’s military service academies as part of an effort to diversity military leadership.

Since this country’s founding, the military has been pitched as the great equalizer — a path to good benefits, solid care, and respect no matter your background. This was too often cynical advertising based on lies. While the work of the military is morally complicated, it is, at the end of the day, a job like any other. Those who make careers out of this work deserve fairness, equity, and support no matter their background.

"Do not forget that the Fascisti are to Italy what the American Legion is to the United States." — Alvin Owsley, Nat. Cmdr., American Legion 1923

Most people likely aren't aware the Legion was created by a group of corporate moguls to provide trained military personnel to assist with the suppression of the labor movement.